The North/South urban divide

The cities of the North and Midlands developed in very different ways to London and its surroundings - and this legacy is still with us today.

A few weeks ago, Tom Forth – a very perceptive and prolific commentator on the economic woes and lost opportunities of the North of England – posted a few maps showing price per square foot for housing in various cities. In London, he noted, the most expensive areas were next to the centre, with prices generally falling with distance from the core. Bristol showed a somewhat similar pattern. In the cities of the North and Midlands, the opposite was the case; with the odd very rare exception, the cheapest areas were in the inner city, the more expensive on the outskirts.

I am sure at this point some people are pointing to the amount of new residential development in, for example, Manchester City centre. This certainly does demonstrate a shift, although I would argue that it is disproportionately driven by younger, single people and is spatially limited. To use the London comparison, it is not as if the price gradient noted by Forth is a result purely of people wanting to live in Westminster.

It is mostly because the inner suburbs - the ones just outside the core - are expensive and desirable; more so, in per sq ft terms, than those on the city’s edge. There is no sign, yet, that equivalent areas of northern or midland cities are following suit. Suburbs such as Charlton or Didsbury are, in relation to the extent of the city, ‘middle ring’ suburbs comparable to Chiswick or Hampstead not Primrose Hill or Chelsea – or even more recently gentrified areas such as Hackney. (The obvious exception is Birmingham’s Edgbaston, but this is due to its unusually spacious and lavish nature and its related status as a ‘great estate’ owned by an aristocratic family, as well as Birmingham’s much more recent economic decline).

A more recent post on Forth’s blog asks why the North and Midlands of England are so poor compared to the South. There’s a long list of historic complaints, ranging from the prohibition on new universities outside Oxford and Cambridge to more recent centralisations of power in London. But he doesn’t connect the two issues – although Paul Swinney at the think tank Centre for Cities hints at it in pointing out that the central parts of the UK’s largest cities outside London – which tend to be in the North and Midlands - are not particularly dense. I’m going to argue here that there is a thread binding all this together – a north/south divide in urban development and the image of the inner city and the relative status of the medium-density urban form embodied by the terraced house.

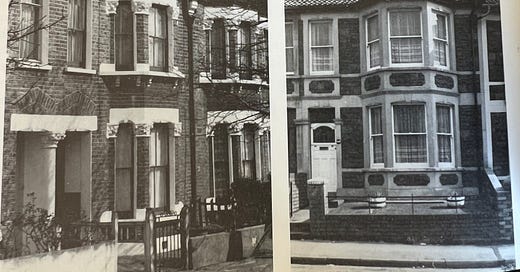

When I first arrived in London in my twenties, I was struck by the nature of terraced housing in the capital. Firstly, there were the obvious Georgian and early Victorian houses, bang in the middle of town or on the edge of it, which seemed to be where some (very) affluent families happily lived. (Bristol has a similar pattern, albeit on a smaller scale.) Meanwhile, further afield, in zones 2 and 3, there were vast areas of terraces which, given their bay windows and ornamentation, must have been built for a much more middle class market than the ones I was familiar with in the Midlands.

Left: A typical late nineteenth-century ‘standard’ London terrace, extremely common in zones 2 and 3. This one is in Coleman Street, Camberwell (1880s). Right: A Bristol equivalent from c. 1890, Coronation Road, Southville.

I wasn’t aware of the reasons for it at the time, but these observations hint at why the divide exists. To understand it, we have to look at the historical development of England’s cities. The way the inner suburbs of somewhere like Manchester developed over time was quite different to their equivalents in London and Bristol, and that partly explains the divide today.

The following necessarily makes a few generalisations in order to explain a general trend. There are of course exceptions, which no doubt will be pointed out to me after this is published.

English anti-urbanism

Despite being living in the first country to industrialise, and in one of the most urban societies on the planet, the English have been notoriously anti-urban for most of their history. Continental visitors to England in the late Middle Ages and early modernity, particularly those from highly urbanised societies such as the Low Counties or Northern Italy, were struck by the lack of town life outside the capital.

The largest cities outside London - places like Norwich and Bristol - were small compared to the largest non-capital cities in the continent. One 16th century visitor, quoted in Asa Briggs’ Victorian Cities, observed that “among the English the nobles think it shameful to live in the towns; they reside in the country, withdrawn among woods and pastures.”

The late planning academic and historian Sir Peter Hall put it succinctly at a conference I was at twenty or so years ago, in a phrase that has stuck in my mind since: “We hate cities; we love suburbs”. It might have been more accurate, though, to say villages and cottages. The writer DH Lawrence put it more floridly: “[The English] don't know how to build a city, how to think of one, or how to live in one. They are all suburban, pseudo-cottagey, and not one of them knows how to be truly urban.”

There are perhaps obvious reasons for this: on an island, you can spread out. You don’t need walls to protect yourself if the next-door country or city-state decides to invade. It’s notable that some of the densest historic towns in England are in places where warfare was more of an issue, close to the coast in Sussex, in the vicinity of the Scottish border, and in the Welsh marches.

Add to this the fact that the English, unlike the Scots and most Europeans, did not really develop a tradition of apartment living, especially not on a grand scale, until very late and then only very partially. I’ve written about the history of all that here:

On the other hand, the Low Countries and northern France don’t have an apartment living tradition either, but that hasn’t stopped them from developing a more urban culture than the English.

Perhaps all we need to do is point to this ingrained anti-urbanism, and argue that London only avoids it because, as the centre of wealth and power around which all the country revolves, it has a strong enough gravitational pull to counteract the anti-urbanist instinct. But that would not explain why similar patterns are clear in Brighton and Bristol, the cities at the heart of the 11th and 15th largest urban areas in Britain respectively. The reasons are deeper and more historical, even if they may ultimately stem from the same source.

Different Settlement Patterns

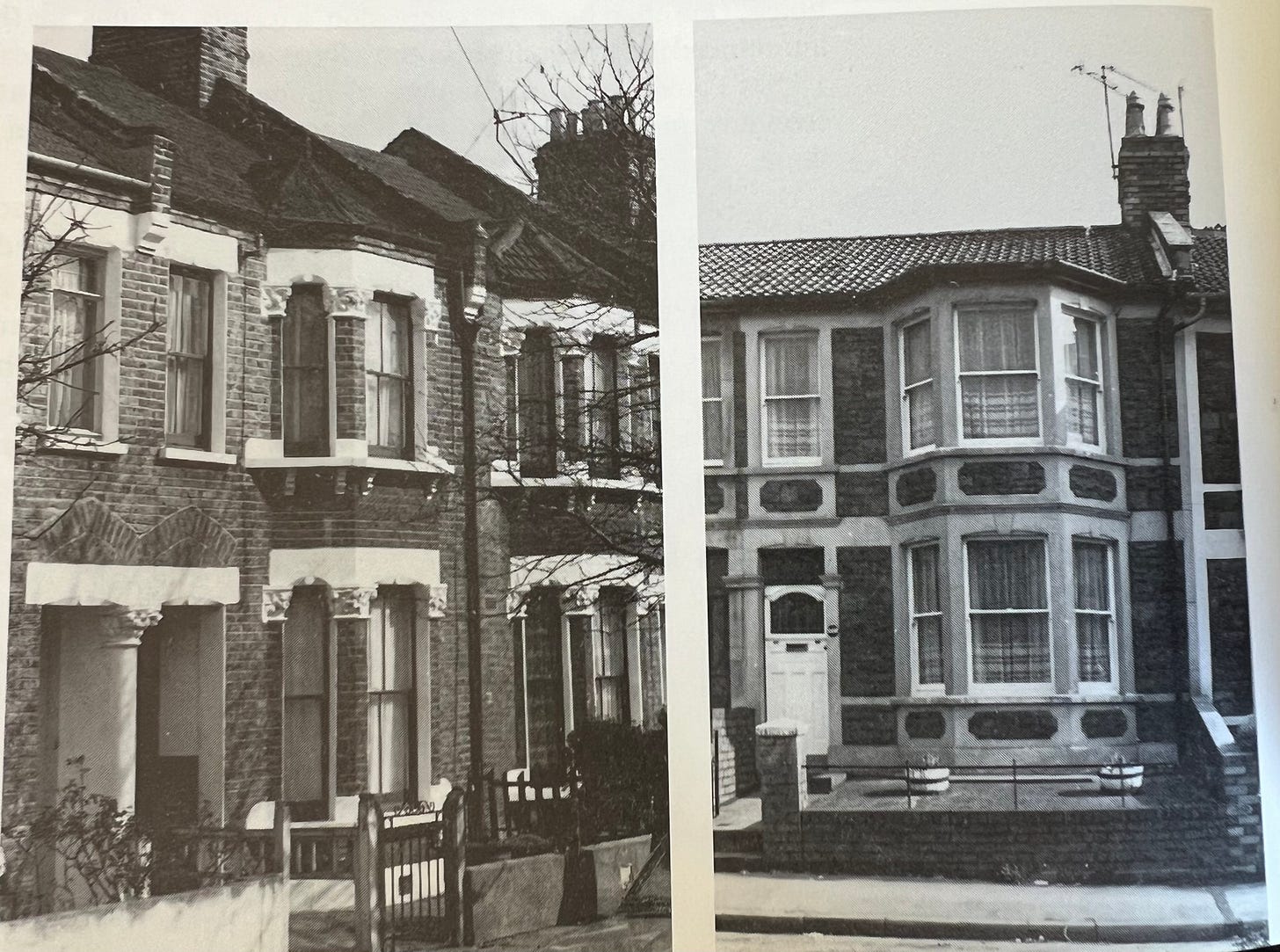

Go back to the Middle Ages, and there would obviously have been two very different settlement patterns in England. On one hand, there were areas – usually the most fertile agricultural areas – where open field agriculture predominated, and people generally lived in nucleated villages, some of which grew into towns. And then, on the other hand, there were areas where farming was carried out by smaller units living in isolated farmsteads, in fields that had been hacked out from the waste (usually woodland; sometimes moorland, bog or fell). This divide was perpetuated by the later enclosure acts which largely concentrated on the former areas.

Now the North of England mostly featured the latter, much more dispersed settlement pattern. The exception was the eastern half of Yorkshire – the East Riding and the Vale of York – which followed the more nucleated model. It’s no surprise that these areas have not only the North’s most important historic city (York), but also some of its other major cathedral cities (Beverley, Ripon) as well as an important port (Hull).

The more dispersed pattern was not confined to the north – it was also present in the far South East (Sussex, Kent, Essex), parts of East Anglia, much of the Welsh Borders and the West Midlands, and the West Country. But the North was perhaps unique in the predominance of the dispersed settlement pattern, and the lack of major settlements. This is clear in the map below, from 1377; the general pattern would not change much until the mid-18th century. Indeed, we can trace out an elongated “U shape” from the Scottish border west of Newcastle stretching down to where the modern West Midlands conurbation is; this area not only has no major settlements of over 1,000 people, it also contains the sites of the major industrial cities of England today – Birmingham, Manchester, Sheffield, Bradford and Leeds, as well as their highly urbanised hinterlands.

Now compare this map with Oliver Rackham’s outline of the ‘planned countryside’ (the previously open field areas that were the main target of the 1700s enclosure acts).

But this anti-urbanism can be exaggerated

The anti-urban theme is often severely overdone, though, particularly by Garden City supporters such as Hall. The late Tudor and Jacobean period saw a ‘great rebuilding’ of towns and the building of many grand houses in their hearts; by Georgian and Regency times England had developed a sophisticated urban culture, not just in the elegant squares and crescents of London, but also in places like Bath, Brighton, Liverpool, Newcastle and Bristol. It would be evident today in Plymouth, Southampton and Portsmouth had they not been so devastated in the war. At the same point many county and market towns saw a revival.

What is perhaps less obvious is that while this was concentrated in the South and in the ports, it was not confined to it. The 18th century development of Birmingham was that of a classically planned Georgian town, as is still discernible in a few fragments. The survival of St John’s Square in Manchester and Park Square in Leeds, if not on the scale of London or Brighton squares, show that this fashion was not just a London thing. Unfortunately this tradition was partly curtailed by the impact of industrialisation.

The importance of Building Acts

There is a difference, though. In London, this urbanity was shaped and supported by building acts that were put in place from the 18th century. These dictated the appearance of homes to some extent - thus the relative uniformity of Georgian London. This was often reinforced by the fact that many houses were built on leaseholds provided by big landowners, who enforced covenants on the physical characteristics of housing. They were invested in the long-term management of their estates, even if in some cases this lapsed severely.

Some cities also passed building acts at the same time, usually modelled on those drawn up in the capital. One, interestingly, was Bristol, another city which today still has some of its most expensive areas near the centre. Liverpool was another, which perhaps explains why the city retains - uniquely in the North – such a large stock of Georgian housing.

In Liverpool’s case, though, this didn’t help the sheer scale of slum, court and back-to-back housing that developed earlier than in other cities; the twentieth century saw it engaged in a heroic attempt to reduce the overcrowding of its housing stock, the worst in the country as the result of its location, immigration and the need for workers to be as close to the docks as possible. This included the early development of municipal flats and the country’s first council housing. Liverpool was unique outside London in its embrace of the flatted block, which is probably not coincidental. (Newcastle also had its ‘Tyneside flats’ but these were two-storey maisonettes built in house form).

While 18th and early 19th century urban development in Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield followed the trends of the time - often through landowners leasing land to builders and/or landlords and applying covenants - they were not backed up by law. There was no bar to the development of the overcrowded back-to-back and court housing which became a feature of the northern and midland cities. That is partly because governance structures were slow to catch up with urban growth.

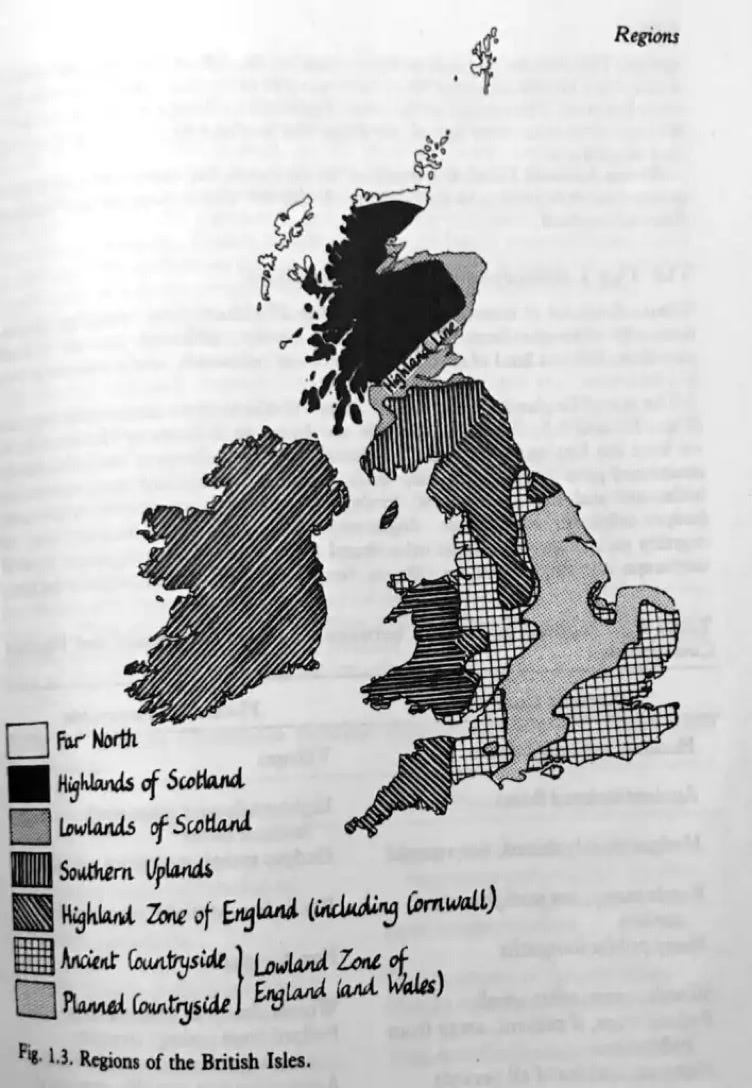

Court housing in Liverpool. Almost all slum terraced housing from before 1870 has vanished. Most surviving working-class terraces are of the by-law period (see below)

So, London’s Victorian squalor was more to do with overcrowding within buildings; larger houses became multi-tenanted; rooms were shared; individual buildings became massively overcrowded. This ‘virtual flat’ tradition may explain why London saw, from the late 19th century, the development of flats both for workers (as in the case of the Boundary Estate) and for the upper middle classes (the mansion blocks).

Of course, there were earlier, denser buildings, which were often even more horrendously overcrowded, and in some places, authorities were powerless to prevent the development of courts. But many of the worst ‘rookeries’, which were largely in the older, most central districts, were demolished through road widening and slum clearance schemes in the mid to late 19th century. Parts of East London around the docks did see dense development, comparable to parts of northern cities - although the back-to-back appears not to have emerged.

The more usual pattern of development in 19th century London was for areas to be built with a relatively affluent, middle-class market in mind (or at least in theory), and for it only briefly (or never) achieve that before becoming severely multi-occupied. This was all supported by high land values, which in turn led to high rents, and encouraged building overcrowding.

In the North and Midlands, the expansion of the 19th century happened in a different way. The lack of building laws – and in some cases the need to be within walking distance of factories – meant that more and more houses were packed into a smaller and smaller space. In some places, this led to ‘court’ housing as the gardens of the older Georgian properties were filled in with hovels, often backing onto the ones built in the adjacent home. In parts of the North, true ‘back to backs’ developed, with streets of tiny terraces built, with the back wall of one house the back wall of the one in the street behind. These areas, even if they had survived, would not have been obvious targets for gentrification.

Court Housing in Birmingham, built early to mid 19th c. The smaller terraces have been built into the gardens of an older house fronting the street.

Then, of course, there is the fact that industry was overwhelming located in the North and Mdlands. So, the cities became dirty and polluted, and most who could moved out; meanwhile, as more people crowded in, the worse the housing situation got. This reinforced the existing anti-urban bias; as one historian of the time observed, comparing a British industrial city not with Europe but with America: "The best society of Philadelphia was trying to improve and glorify Philadelphia. The best society of Manchester was trying to get out of it.'

London, of course, was notoriously smoky and smoggy – more so than cities elsewhere - but the quality of the built environment, and the visible sanitary conditions, while dire, perhaps not so immediately shocking, except in a few parts of the East End and some isolated rookeries. More importantly, the more all-pervading squalor of inner-city Manchester or Birmingham defined the problems of the city for housing reformers, perhaps even more so than London’s slums, and they would be a particular target for sweeping clearances.

The housing by-laws

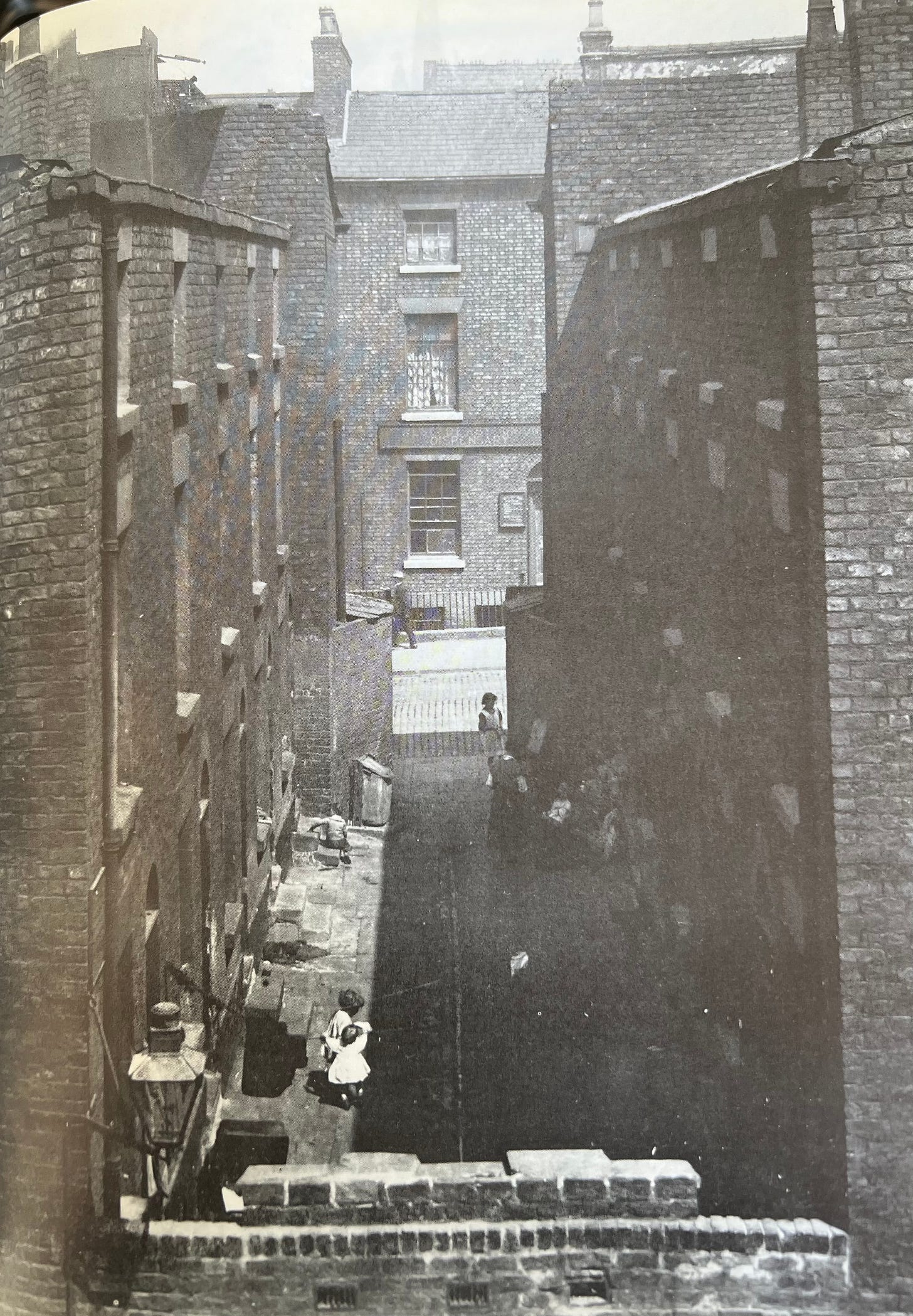

This all changed to some extent with the mandatory introduction of housing by-laws in the 1870s. Local authorities had to enforce minimum standards; indeed, builders had to submit plans to councils for approval, the distant precursor of today’s planning consent. This led to the building of terraces that often conformed to these minimum standards, leading to a high degree of local homogeneity and grid-pattern streets, something hated by later housing reformers.

Later Victorian by-law terraces in Manchester. Note the lack of gardens compared to London terraces of a similar date. These are often called ‘back-to-backs’ but this is a misnomer.

These ‘by-law’ terraces form the vast majority of surviving working-class terraced housing in our cities; the earlier examples almost entirely vanished in waves of largely post-war slum clearances. (Most by-laws banned back-to-back housing; this was resisted in West Yorkshire, particularly Leeds, where ‘improved’ back to backs were developed through their versions of by-laws. Even when the 1909 Planning Act banned them nationally, they carried on being built in Leeds until the 1930s, as so many had already been consented through the by-law system).

Later back-to-back housing, Leeds

The by-laws enforced minimum standards, sizes and street widths for housing; in practice they became the maximum too. The result was very standardised, plain housing often criticised for its monotony. London’s terraces of the same date are more likely to have bay windows, higher ceilings and both front and back gardens - a result of their more affluent and diverse target market. There was a larger middle-class, and more importantly, they were prepared to live in terraced housing, not just because the basic product was better, but also because there were still extremely high status areas in central London - such as Kensington or Knightsbridge – where the terrace was dominant.

Meanwhile, in the North, terraced housing had developed an image problem, thanks to back-to-back and then by-law housing. It was associated with poverty, pollution, and with various other ills of the city; if you were rich enough, you didn’t live in the middle of the town, and you certainly didn’t live in a terraced house. The by-law terraces were a massive improvement, but their alleged monotony, lack of light and air, and their deeply working-class associations only reinforced some of these perceptions.

Rows of by-law housing, Preston - similar scenes made up most of the inner city in Manchester and other northern industrial cities.

Of course, there are some better quality terraces in parts of the northern cities, but they are nowhere near as widespread as in London. Generally, the late Victorian middle-class suburbs of the North and Midlands tended to develop around semi-detached and detached homes, rather than terraces that were still being built for similar people in the South; this was all possible because the middle-class was smaller, in relative terms, and probably more keen to distinguish itself from the workers with symbols such as housing types. In some cities, greater upward and downward social mobility than in London may have sharpened the need for visible status signals.

From late Victorian times on, respectability meant living in at least a semi-detached house; terraces were, unlike in the south, deeply non-U. In contrast, the fact that the most prestigious parts of the capital were composed of terraces – albeit on a grand scale – made the building form more acceptable for the middle classes, even if they were more modest.

The garden city movement and then the huge wave of suburbanisation in the 1930s - in which the urban area of British cities increased by around 50% - reinforced some of the anti-urban tendencies in English life. Reformers such as Raymond Unwin emphasised the importance of ‘open development’ – rejecting the feeling of enclosure that partly defines the look and feel of a city. The housing reformers’ ideals had come to life through the market; as the garden city and model village pioneers had wanted, the by-law terrace and the corner pub were replaced by cottage-style housing and gardens. This was the new respectability, something that would become a persistent image in British life.

While suburbanisation was more pronounced in the South, London’s most fashionable districts remained so, and towards the end of the 1930s there was a wave of new flats in the city. In the North and Midlands, though, the new suburbs reinforced the abandonment of the inner city. It became, to use contemporary language, residualised.

Demographic analysis of Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Leeds and Sheffield from the 1951 census reveal that some stereotypes had some truth. Leeds had the largest middle class; Birmingham the largest skilled working class; Liverpool the largest unskilled working class. But one thing was also apparent: they all had proportions of sociodemographic classes I and II that were lower (sometimes significantly lower) than the national average. This was different from London, Bristol and Brighton and even more markedly different from most cities on the continent.

Slum Clearance and Gentrification

Perhaps the most significant change, though, was yet to come. The planning ethos of the post-war period was more resolutely anti-urban than ever. The inner cities would be cleared of congestion, rebuilt at lower densities and with more humane housing, and some of the existing population moved out to new towns or overspill estates on the outskirts - joining those who had already chosen to leave for the old suburbs.

This was the era of “comprehensive redevelopment areas”, as defined in the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. The most blanket use of these powers would be in the inner cities of Manchester and Birmingham. In both cases, almost all of the Victorian inner city vanished, to be replaced by new development, sometimes towers, sometimes low-rise deck-access estates, sometimes maisonettes and houses. It was mostly, despite the occasional high-rise, lower density than what it had replaced.

Some of these areas were genuinely slums and needed to be cleared. But it appears that as a result of the hatred of the old, the hatred of Victorian aesthetics, and the reputation of back-to-back and by-law housing, a lot of better-quality housing was demolished, too - properties that could have been refurbished and repaired. What replaced it was in many cases exclusively council owned.

What remained of the diversity of the inner city was further damaged. In Birmingham’s Ladywood, for example, some professionals - doctors or teachers - still lived in the area, often in the more spacious, street-facing properties or in the better streets (admittedly, they were often small landlords too). The estates that replaced them were more homogenously single-class. This pattern was repeated elsewhere in the country. There was little to no private development in these areas after the war, little or no demand for private housing; residualisation was complete; you only lived in the inner city if you had to. This was compounded by the economic woes of the 70s and 80s; aspiration in the North and Midlands meant outer suburbia or the countryside.

There were, of course, comprehensive redevelopment areas in London, too, often around bomb sites (much more numerous than in other urban areas) and some of the worst slums in the East End, such as Stepney, as well as parts of inner South London. But the city was simply too big for these to have the same impact as in the North and Midlands.

Meanwhile, while the 1960s saw a lot of opprobrium towards Victorian architecture – and the values they were assumed to represent – Georgian buildings were reappraised and revalued much earlier. Indeed, in documentaries post-war redevelopment it’s quite common to hear architects praising pre-1830s building and then condemning Victorian building. Redevelopment plans often made provision for the preservation of good quality Georgian properties, unlike their Victorian equivalents.

This supported the gentrification of London, Bristol and Brighton, where large areas of such homes remained in areas that were not condemned as woefully overcrowded; outside Liverpool, which had its particular problems, the surviving Georgian areas of the Northern and Midland cities were in areas that had seen dense development around them, and were condemned as slums. More importantly, there were very few surviving areas which had maintained the consistent Georgian appearance of some parts of London, other than Bristol and some seaside resorts.

By the 1960s, young middle-class people started moving back into inner city London, buying those older properties in particular and refurbishing them. Notting Hill and parts of Islington – which at the time had very poor reputations for overcrowding and poverty – were the first to see this trend. The term ‘gentrification’ was coined by the sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe what she saw happening in Barnsbury and Canonbury. This process accelerated in the early 1970s with the Barber Boom, which while disastrous in economic terms provided these young gentrifiers with the cheap mortgages they needed.

Myddleton Square, Islington: The original gentrification (Wikimedia Commons)

Inner city terrace living (preferably Georgian) was becoming synonymous with a certain kind of young professional existence, which would later be called ‘yuppie’. As Victorian architecture was reappraised in the 1960s and 1970s, it was easy, in London, for this to be transferred to the spacious late 19th and early 20th century terraces of zones 2 and 3 – the Claphams, the West Hampsteads, and so on. It would later spread throughout most of inner London.

Admittedly this did happen in somewhat later in the north and Midlands too, but it was confined to a few ‘middle ring’ suburbs that had originally been built as outer, semi-rural ‘villa’ suburbs for the management class. They had in some cases become run down and dominated by bedsits, and had often seen infill with 1930s-style semi-detached or detached homes - but they had not seen the court developments and their terraces, where they existed, were of the by-law era.

Moseley and Harborne in Birmingham, Didsbury and Chorlton in Manchester, or Chapel Allerton in Leeds all saw gentrification to some extent – but they were much smaller in scale and geographically highly concentrated. Again, the 1980s did see the start of a city centre revival, with homes being developed privately for the first time in genuinely inner-city locations such as Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter and Manchester’s Castlefield. But again, this was highly geographically concentrated and only served to emphasise the fact that much of the inner city was, unlike London, not seeing these trends.

The reason, if it needs spelling out: because of all the historic trends mentioned above, the quality of housing, and the resulting quality of place, were rather different. This spilled over into a north/south cultural divide over housing preferences and the acceptability of density. Even today, a typical terrace in London is worth 11% less than a semi-detached; in the East of England the figure is 19%; in the North West it is 28% (figures from Land Registry).

Transport Policies

Post-war transport policies also exacerbated these trends. Vast roadbuilding projects were put in place across the country, including urban ring roads. The first stretch of motorway was built near Preston and in comparison, to the population far more of the network was built in the northern half of England. It was simply easier to build them, especially into and out of northern and midland cities, partly because of the extent of the comprehensive redevelopment areas of the same era. Meanwhile, tram systems were ripped out and train lines closed, while the Underground and most London suburban lines continued operating.

As Peter Hall astutely noted, the motorway network had far more of an impact in the North than in the South-East, allowing people to live much further away from their work than ever before. This encouraged a much more rapid middle-class exit from the cities.

There are of course exceptions to this pattern, such as in Newcastle, with its Tyne & Wear Metro and a handful of desirable inner suburbs. But that city and its surroundings (as with the other great port of the North, Liverpool) was always different, with its ‘Tyneside flats and planned centre – making it more similar to the much more continental urban traditions of Edinburgh or Glasgow than any English city, perhaps unsurprising given its location. But in the inland industrial cities, it held true.

The radial motorways did have an effect on London, of course, but it was much less pronounced outside perhaps the M4 corridor. The attempt to build urban motorways (the ‘motorway box’) largely failed in London as a result of the sheer cost and, to some extent, the fact that the areas proposed to be demolished were rapidly gentrifying and their values increasing. This process also meant slum clearance was never as total as in some of the northern cities.

As services job numbers rose quickly in London in the late 50s and 60s it became apparent that it would be impossible for everyone to commute into Central London by road, as was the assumption in other cities – despite attempts being made to clamp down on office development in the centre. There were far more car-borne commuters than today, but rail and tube remained the main form for most people, unlike in the rest of the country. By the seventies it was apparent that this was not going to change, thus the decision to invest in the Victoria Line, which completed in 1971.

The combination of relatively dense (and desirable) inner suburbs, dense central employment and the critical role of public transport has created a self-reinforcing mechanism that is hard to break – or to copy. (Rather ironically, in the 50s and 60s, this was thought of as a huge problem, but as agglomeration economics is now better understood, it looks more like a virtuous circle).

It must nevertheless be possible to get such a cycle starting in the northern and midland cities. Manchester, with its relatively extensive tram system, probably has the best chance, although capacity remain limited and car-borne commuting is still very important. The best way to create this would perhaps be to allow the development of more medium-rise flats on the fringes of existing affluent middle-ring suburbs, but this will face more NIMBY-esque challenges than city centre development.

It's become a bit of a trope, on social media as well as its conventional form, to bemoan the state of English cities, particularly in comparison to their continental equivalents. There is often a suggestion that this represents a decline from some earlier state. Few seem aware that in this country the city has always been seen as an unfortunate necessity to be managed, particularly in the North and Midlands.

For example, in 1962 - when gentrification was just starting in London - the Guardian wrote: “The North is crippled with the burden of the Industrial Revolution to an extent that the South hardly begins to understand. Virtually the whole social capital of the northern towns, from the antiquated town halls of marble and millstone grit to the grimy schoolhouses among the streets of back-to-backs is.. in desperate need of renewal. The sheer mental depression.. is enough to deter most professional people from the South from ever settling in these towns.” In the same year, the Economist proposed curing the north-south divide by creating a new capital between Leeds and York. Sound familiar to anyone?

Indeed, there has not been a time when the inner city areas of the main conurbations of the North and Midlands have not been seen as problematic – from the writings of Engels in Manchester’s slums, via the vast slum clearance programmes of the early to mid-20th century, through the panic over the state of the inner cities seen in the 1970s and the 1980s, the ‘urban renaissance’ of New Labour, and so on. These various initiatives have had some success, but it has been highly geographically concentrated. Those bemoaning the state of British cities today should bear in mind there was no ‘golden age’ for these inner cities, unless we go back to the 1700s and very early 1800s; they have, for two centuries, been places that shocked mainstream British life, places where you only lived if you could not avoid it.

For whole periods in the 20th century the term ‘inner city’ was synonymous with poverty and crime, something that would have seemed odd in many neighbouring countries. Without acknowledging this history, it’s tempting to assume today’s issues are something new – and that more radical solutions might be needed if we want to see a real urban revival (and an economic revival) in most of the big cities outside London.

It is an interesting take, but I'd be wary of two things: reading backwards from the current standing terraced housing, and using such big units of comparison.

As Alan Crosby has pointed out, the majority of standing Victorian housing dates from after 1870 i.e. after the impact of the housing by-laws you rightly discuss. It's the good stuff that has survived by-and-large, and certainly in the East Midlands much of this stock was intended by its private developers for skilled workers, clerks and the shopkeeper/tradesman class, rather than manual workers. Commentators in the 1920 and 1930s were pretty favourable to Northampton, Leicester and Nottingham. Before 1940, people said very nice things about Coventry. The main criticism of these places were that they were a bit dull, rather than that they were horrible.

The problem with comparing everything to London is that the capital was so much bigger in population terms than other British cities from 1700 to now. It performed multiple national and international functions within one city, so contained overlapping economies and multiple urban landscapes.

It had a large middle class and a large working class. Some areas match your line of analysis, but others, such as outer north-west London don't. Wembley, Northolt, Ruislip can be no one's idea densification. They were also widely criticised in the 1930s and 1940s because of this.

As someone who has moved in the opposite direction to you, my main observation about the cities of the East Midlands, is the amount of underused ex-industrial sites, joined since 2008 by under-used retail and office space, not the lack of people living in the city centre. Most of the industrial sites of West and North London have left no trace, because of the scale of re-development in the 1980s and 1990s. This hasn't happened in parts of the Midlands, Sheffield, the West Riding and Lancashire. This seems to me a problem of the economic base, not the housing stock.

This is amazing stuff - the sort of history writing I love.